Design and magic intersect on 52 small canvases.

By Susanna Baird

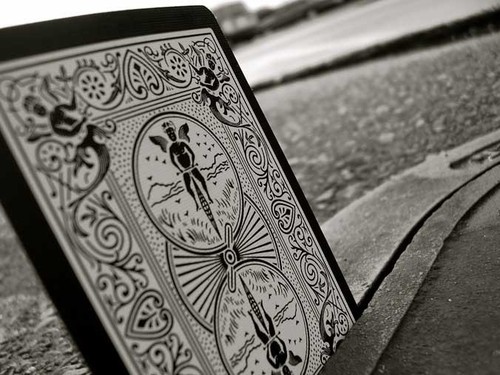

Lee McKenzie’s Empire deck, funded via Kickstarter

Tim Silva owns more than 750 decks of cards. The designer and amateur magician carries a deck everywhere, spending three to four hours a day with cards in his hands. “I sleep with cards under my pillow,” he jokes.

Silva’s fascination with cards and card tricks began when he saw David Blaine's 1996 Street Magic TV special, and exploded into a hard-core hobby after high school. A proponent of straight living — no alcohol, no smokes — Silva wanted a social lubricant. Magic worked! And then, he says, “I just fell in love with magic and cards.”

Search Dribbble: Silva is not alone. March saw 20 shots tagged “playing cards.” Dribbblers including Simon Frouws, Curtis Jinkins and Lee McKenzie have created high-profile decks for online magic communities Ellusionist and theory11. Ellusionist’s Creative Director Mike Clarke uses Dribbble, as does theory11 Founder Jonathan Bayme. Looking beyond the magical, Dribbble designers have created cards featuring everything from creative riffs on the traditional (Roni Lagin's Density deck) to the metal fantastic (Mechanical 3D Metal Playing Cards by Dale Mathis).

Roni Lagin’s Density deck, funded via Kickstarter

Spurred by sensational designs, magicians have become collectors, purveyors and patrons. TV and movie producer JJ Abrams recently teamed with theory11 to create the Mystery Box, a handcrafted lockbox containing 12 mystery decks, including a pack from Luke Bott. Illusionists Dave and Dan Buck of online magic hub Dan & Dave launched Art of Play, “a collection of the finest playing cards in the world, featuring hand-painted works of art, award-winning design and illustration, and luxury packaging.” Popular card designs have become franchises, available not only on decks but also on T-shirts and iPhone cases.

While Silva doesn’t design cards, his appreciation of them stems from the connections he finds between his profession and his hobby. “Magic, like design, is about discovering a balance between problem solving and aesthetics in order to arrive at a presentable solution,” he said. Silva finds that “presentable solution” in a well-designed deck of cards.

With cards, designers face several constraints, including a small canvas and necessary features that must remain legible and in fixed locations. Factor in a magician’s additional considerations — audience, venue, trick — and the design parameters tighten.

Card Design: A Brief History

Playing cards date back to 9th century China, and arrived in Europe 500 years later, possibly via Africa or the Venetian trade.

For a time suits varied widely. Decks from Islamic countries featured cups, swords, coins and polo sticks. “Latin” decks, used in Spain and Italy, bore chalices, swords, money and batons. Hearts, acorns, hawk bells, and leaves covered Germanic decks. A 15th century French illuminated set, one of the world’s oldest surviving decks, is marked with hunting horns, dog collars, leashes and nooses.

Today, much of the world plays with cards bearing the 15th century French-born club-diamond-heart-spade combination. Over time, card makers simplified the suits so they could stamp the cards, an easier and cheaper alternative to woodcutting.

The Diamonds from Rick Davidson's Origins, funded via Kickstarter and inspired by 15th century French decks

King James I of England (17th c.) brought branding to the deck, demanding an insignia on the Ace of Spades as evidence of taxes paid. The joker showed up in the 19th century, and symmetry became the norm. For many centuries, cards had a “right side up.” With symmetry, upside-down cards became a thing of the past.

Also in the 19th century, card makers added numbers and suits to card corners. These indices allowed players to hold cards fanned close together in the now-familiar fashion; the first decks were called “squeezers.”

Illusionists have been performing card tricks nearly as long as card makers have been making cards. Leonardo Da Vinci’s friend Luca Pacioli wrote the oldest trick in a book, introducing card tricks in his late 15th century treatise De virus quantitates (On the Power of Numbers).

Despite the long partnership between cards and magic, card makers didn’t give much thought to the design desires of illusionists until the last decade.

Magic and Card Design: Function

According to illusionist Marco Tempest, an estimated 70 percent of magic tricks involve playing cards. A magician bases deck choices on a variety of factors, including trick and audience. Many magicians will tell you the most important thing about a deck isn’t seen, but felt. “Above else, I want a deck that handles well,” said Tim Silva.

Tim Silva flourishing with a deck of Tally-Ho Circle Backs.

A playing card is typically made of a few layers of paper sealed together and treated. (Tricksters sometimes take advantage of this fact by card splitting, stripping the cards apart and refashioning in ways that help this trick or that.)

To the uninitiated pair of hands, one deck of cards feels fairly similar to the next, but card manipulators such as quick-handed illusionist Jason England can easily differentiate such tactile characteristics as paper thickness and cutting style.

Dribbble talked to England at his home in Las Vegas, where he consults with casinos on card cheats. He also contributes to theory11 and is well-versed in magic history. When we spoke, he was preparing for a trip to Los Angeles to perform for Bill Clinton.

Jason England, magic historian, illusionist, casino consultant, theory11 contributor

"You could give me a set of [golf] clubs that Tiger Woods uses and a set from Walmart and I couldn’t tell them apart, but Tiger Woods could," he said. "If I gave you 10 decks, you couldn’t tell them apart, but I can."

In addition to thickness and cut, card handlers pay close attention to a deck’s finish. Cardistry is the art of non-magic card handling, or flourishing. Think extreme shuffling: fans, one-handed shuffles, cascades of cards flying through the air. (Our favorite flourish is the dribble, featuring a card waterfall.) Flourishers who need cards to slide across one another, finish is especially important. Ideally, cards will glide as if each is a mini hovercraft, with a minute cushion of air in between each.

"If you go to Walgreen’s and buy a novelty deck of GI Joe cards, they are cheap and they feel like plastic," Silva said. "With cardistry … if the cards clunk up, if it’s a bad deck, some of the cards are going to be stuck to each other, some of the cards are going to slide apart."

Many maneuvers benefit from specific card features. Second dealing involves a magician dealing the second card in a deck, while appearing to deal the top. Borderless cards such as the traditional Bees and Mike Clarke’s Republics, with their pattern stretching all the way to card’s edge, make a second deal easier to conceal.

Mike Clarke’s Republics, from Ellusionist, feature a borderless back.

Magic card makers produce gimmick decks for various brands of trickery. The one-way force deck holds 52 of the same card, sometimes with a different top and bottom card for decoy. Magicians use the deck for simple “pick a card, any card” tricks.

A stripper deck features cards that are subtly tapered at one end. The reduction is so slight as to go unnoticed by the audience, though a practiced magician can feel the difference and can flip cards he’d like to find later.

Invisible decks include top-secret alterations, the details of which this unmagical reporter couldn’t conjure. Magicians employ invisible decks in a variety of “I can guess what card you’re thinking of” tricks. Pioneering 20th century magician Joe Berg, whose Hollywood shop served as a salon for mid-century magic’s in-crowd, invented the deck. His name for it — the Ultra Mental Deck — didn’t stick, but his deck and related tricks are still considered industry staples.

Magic + Card Design: Aesthetics

USPCC’s Bicycle Rider Backs; photo courtesy theory11

Traditionally, American magicians have shown a strong preference for the United States Playing Card Company's Bicycle Rider Backs, on the scene since the end of the 19th century. The familiar card backs feature pedaling cupids atop tall and slender bikes; the same red-and-white or blue-and-white cards that sit in your junk drawer, on your grandmother's card table, in a spinning rack near the magazines at the corner store.

It’s this total lack of special that Jason England wants. He plays with all manner of decks in the home office, but when he performs he needs a deck that people trust.

"I want to put in front of my audiences a deck of cards that they’ve seen before, that looks like maybe I bought them at the drugstore," he said. "What I’m after are those iconic and historic designs." Bicycle Rider Backs and Tally Ho’s Circle Backs fit the bill.

All three decks feature designs that are the same coming and going. This characteristic is another visible means of breeding trust with an audience, says Mike Clarke of Ellusionist. “No matter what way the card is inserted into the deck, it will blend in and not have a visible design difference that may catch the eye of a spectator and lead them to believe you are using a trick deck,” he explained.

While England and Clarke seek normalcy in a deck, England said the next wave of magicians craves a little more excitement, buying $30 premium decks and holding on to them for as long as they last.

Curtis Jinkins’ Monarchs, from theory11

Enter Silva, who holds on to his decks for up to two months or, in his estimation, 100 tricks. When discussing his own preferences, he talks like the designer he is. “I’m obsessed with minimalistic cards, decks that have a flat aesthetic to them,” he said. “Too many details, like the overuse of shadows, I find distracting when printed.” Silva also appreciates classic card design elements such as curls and flares, citing Curtis Jinkins' Monarchs. “Those cards are brilliant,” he raves. “I love how pure the back design is. It’s just so rich in monochromatic illustrations.”

To a great extent, card preference boils down to what a magician wants to say. England asks his decks to whisper “trust me,” while another magician may want his cards to express his onstage persona or serve as well-designed cover for the workings of an illusion. Many magicians employ multiple decks throughout their acts, choosing the best deck to meet each trick’s challenges.

The Black Tigers and Beyond

Interested designers have been able to custom-make cards for more than a century, though both effort and cost were prohibitive. “At any point throughout U.S. Playing Cards' history, if you went to them and said, 'Here's some artwork, I want you to make these cards for me,' they would say, 'No problem,' said Jason England. “They may say, 'Well you have to buy 5,000 decks.'”

Despite the obstacles, magicians have been creating custom decks for years, often gimmick cards or decks imprinted with their logo. Occasionally a unique magic-universe deck or two would leak out, but “no one ever thought to make cool, new playing cards,” said England.

Until 2007, when Ellusionist released its Black Tigers.

Ellusionist’s Black Tigers

Along with Tim Silva and “9 million other people,” Ellusionist CD Clarke discovered magic via David Blaine’s 1996 special. To learn more, he turned to Ellusionist. Clarke’s plan? Blow some minds. “I spent the next four years of high school doing card tricks for anybody who would watch.”

Back then, Clarke never imagined the role design would come to play on the magic scene. “I never, nor did a lot of people, expect customized playing cards to be such a large part of the magic industry,” he said. “It all started with the Black Tigers … . That was the very first customized Bicycle deck for magicians.”

Designed by the team at Ellusionist, Black Tigers feature the familiar Rider Back with a startling change: The cards are black, with features in white or red depending on suit. Upon first viewing, the cards deliver the same disconcerting jolt one receives when looking at a photo negative of a good friend. The deck is at once familiar and alien, hinting at a mysterious upturning of the regular order.

“Performing magic back in the mid 2000s, the Black Tigers probably evoked more attention and comments than any deck before,” Tim Silva said. “This was the first mainstream deck in magic that didn’t communicate ‘trust me’ to spectators.”

The Tigers startled audiences and won magicians by simultaneously inverting and respecting tradition. But it wasn’t this deck that marked a shift, argues Clarke. It was all the decks that came next.

"I think the moment the magic community started ‘coveting great design’ would be when not only Ellusionist was designing cards, but when the industry followed," he said. "The Buck Twins [Dan & Dave] have made a massive impact in design and contribution to this world with collaborations with iconic artists and have certainly pushed the envelope in card design from the cards themselves to the packaging they come in."

Card makers awoke to design and came knocking, holding out 52 tiny canvasses and inviting input. Card makers such as Jonathan Bayme.

Rise of the Guardians

Like Silva and Clarke, Jonathan Bayme found magic via one of its top practitioners: David Copperfield. Known for his grand-scale illusions, dramatic showmanship and hip persona, Copperfield epitomizes late 20th century magic, wherein the illusionist plays not only the trickster but also the rock star. When five-year-old Bayme saw him perform live, he was hooked.

"I was blown away," Bayme, now 26, remembers. "I was immediately and totally obsessed with magic." Charleston, South Carolina offered little in the way of a magic community but between the library and trips to a magic store in Myrtle Beach, Bayme cobbled together an education. By the time he was in middle school he was performing to full houses around the southeastern United States.

Bayme worked for Ellusionist in the early years of this century, then joined with several other magicians to found theory11 in 2007. Soon after, they launched their own attention-grabbing deck, the Bicycle Guardians.

Justin Kamerer’s Bicycle Guardians, from theory11

"Everything about theory11 is intended to advance the art of magic. Part of that is style," Bayme says. "As a magician, it’s a little hard to look badass if you’re using standard Bicycle cards that have baby angels on the backs. So that got us thinking - what if we designed a totally custom deck of playing cards? Back design and all."

For the Guardians, Justin Kamerer riffed dark and bold on Cupid, creating a powerful card-back angel clutching a spear, staring down at the demon he’s crushed. Magicians, amateur and professional alike, were wowed.

Theory11 now views the design process as integral to card making as the manufacturing process. Finding new designers on Dribbble and Kickstarter, Bayme and theory11 always have new decks in the works. Ellusionist keeps pace, aiming for a new deck a month.

In 2014, a motivated designer can create a deck in an afternoon and, relatively cheaply, order a run or throw the design up on a crowd-funding site such as Kickstarter or Indiegogo. Taking the trend a step further, Dan & Dave are currently working on DeckStarter, a crowd-funding site for cards, card and nothing but cards.

Clarke the designer and Clarke the magician both celebrate a crowded card-design market. “With the enormous amount of competition, you really have to think outside of the box when it comes to design,” he said. “There’s so many possibilities and themes that haven’t been touched yet. I’m excited to see how designers push the envelope of a 500+ year old pastime.”

Inspired Community

At the same time as they advance the dual causes of design and magic, online communities gather not only professional illusionists, but also the weekend magicians: lawyers wanting a few party tricks, soldiers stationed far from home, shy kids who want to impress their friends.

"Magic has a rare power to it unlike any other artform. With just a few great tricks and practice, you can literally go from being the introverted kid to the life of the party," Bayme said. "Our goal at theory11 is to share that feeling, that ability, with as many people as possible - it’s like a superpower. We sell superpowers."

Superpowers are super, and so is magic, but Tim Silva argues that what makes theory11, Ellusionist and other online magic hubs successful is what makes Dribbble successful: involved, inspired communities. “Before Dribbble started, there was no credible design community that excited me,” he said. “That was, for designers, a cultural revolution. It takes a long time for something like that to come along.” The same holds true for the world of magic.

"It takes a long time for people to orient themselves [magically]," Silva said. "When they started these websites, it was monumental. I think magicians are lucky to have access to these free, invaluable hangouts."

Want more? Next week we will feature Q&As with card designers Simon Frouws, Curtis Jinkins and Lee McKenzie, plus on-deck commentary from Tim Silva.

![]() A giant thank you to Tim Silva. His magic tricks at the 2013 Dropbox + Dribbble meetup led to this story. He’s been an invaluable source of information, perspective, and cheerleading since minute one. His thoughtful reading also led to a healthy thickening of a few previously skinny portions of the article. Thanks also to Mike Clarke, Jason England and Jonathan Bayme for their input and time.

A giant thank you to Tim Silva. His magic tricks at the 2013 Dropbox + Dribbble meetup led to this story. He’s been an invaluable source of information, perspective, and cheerleading since minute one. His thoughtful reading also led to a healthy thickening of a few previously skinny portions of the article. Thanks also to Mike Clarke, Jason England and Jonathan Bayme for their input and time.

Find more Updates stories on our blog Courtside. Have a suggestion? Contact stories@dribbble.com.