Episode 1

Episode 1: Ian Brignell

Overtime is Dribbble’s audio companion and our first foray into the world of audio. In this interview, Dan speaks with letter, logo, and font designer, Ian Brignell.

Ian’s impressive client list includes Budweiser, Smirnoff, Harvard, Dove, Hershey’s and many more. We were honored to talk to Ian about his background, his process, tips for designing and lettering, collaboration, and his advice for young designers.

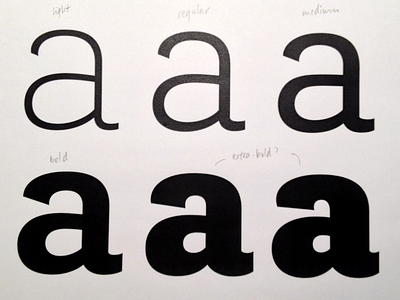

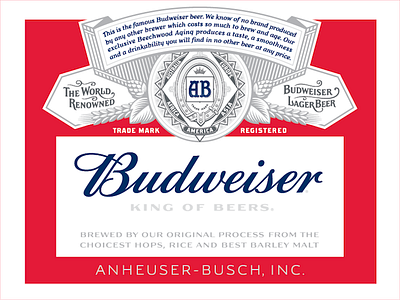

Dan also asks Ian about a few of his Dribbble shots and the story behind them. Ian shares his process for designing the Coke font and the Budweiser label pictured above. He also told us about his font foundry, IB Type, where he has fonts for purchase. So, not only can you admire Ian’s great work, but you can use it in your next project.

It was a really great conversation and we’re excited to share it with you. Enjoy!

Subscribe on iTunes or Download audio via Simplecast

Links Mentioned in Overtime

- ianbrignell.com

- Ian on Dribbble

- IB Type Foundry

- Speedball Lettering Book

- Lettering for Reproduction by David Gates

- Namiki Falcon Pen

Transcript

Dan Cederholm: Welcome to Overtime. This is Dribbble’s audio companion and this is our first foray into the world of audio. Today we are going to talk with Ian Brignell, and Ian is a letter, logo, and font designer from Toronto, Canada. His client list is kind of mind blowing. Let’s just put it that way: Budweiser, Smirnoff, Crown Royal, Miller High Life, Coors, Harvard, Duracell, Dove, Vaseline, Burger King, Hunt’s Ketchup, Bower, Chopstick, Playtex, Hellman’s Mayonnaise, Estee Lauder, Swiss Chalet, Hershey’s. The list goes on and on. The guy is amazing and should be a legend, and should be a household name.

We were really honored to be able to talk to him today—talk to him about his background, his process, tips on designing, lettering, everything. It was a really great conversation and we’re excited to share it with you today. Without further ado.

Welcome, Ian Brignell, thank you so much for taking with us today.

Ian Brignell: It’s my pleasure, Dan.

Dan: It’s super exciting for us because we have not delved into the world of audio before. For us to be able to talk to you for that first time is pretty amazing. It’s actually quite an honor because your work is ubiquitous, it’s everywhere, and we’re big fans. You’ve just joined Dribbble recently, which we’re quite excited about. I think there’s a lot of questions that come to mind when you say hey, you’re going to be able to talk to Ian Brignell, this super talented designer.

Just to start things off, I’d love to know a bit about your background, your upbringing, and childhood, and whether design or fonts or lettering was something you were interested in as a kid.

Ian: As a kid, my main interests, besides sports and watching television, was drawing. That’s I think where everything started was an interest in drawing and sketching, doing cartoons, all that kind of thing. So I always had sketch pads. I always had markers, pencils, whatever I could get my hands on. I was always drawing things.

That, as it turns out, is pretty much the fundamental skill for lettering too. That’s the starting point. But it’s funny, there was this one incident, I remember in grade four. I was in reading class. I was kind of bored by the book we were supposed to be reading.

I found myself staring at the type, 16-point Century type that was printed on the book. I wondered could I draw that stuff. So I grabbed a pencil and tried to copy it. And I guess whatever the result was, it was good enough, that I thought wow, people can draw letters. It was one of those funny moments in my little grade-four brain, when I knew that books were printed by these huge machines. I kind of assumed that’s where the type came from.

When I drew letters and they actually looked kind of like the letters, something went off in my head. I thought man, the world just changed. That was its own funny little moment that I think kind of started it, but what really happened was around grade nine, I was in art class in high school and the teacher did a two-week course on calligraphy. Broad pens, ink, she brought in the Speedball Lettering Book as a sample book of styles that you could do. Speedball Lettering Book had methodology for creating the letters, how to form them, which strokes to use.

I totally loved it and couldn’t believe that these really simple tools could make these amazing textured, satisfying, dense letters. That was really the—I feel very lucky that that happened with that teacher, at that time, because I was completely smitten with calligraphy, and what you could produce with these tools.

Then I started to do the graduation certificates for the school. I started to do sign painting for local businesses. That was the beginning of a career in lettering design.

Dan: That’s cool. It’s neat that you latched onto fonts and typography so young. I think it’s one of those things most people overlook and don’t think about. They see it and they absorb it, but they don’t really think about the fact that letters look different, and there’s different fonts. That’s cool.

Tell us about the Speedball lettering book. Some folks might not know about it. It sounds like a good resource though, or would you recommend that for someone getting started?

Ian: The Speedball Company was a company that made metal nibs, pen nibs. They made all kinds of them, different shapes and sizes and whatnot. I don’t know when the first one started. I’ve got one from 1952, but I think they probably started in the ’40s, maybe earlier. Someone out there knows the answer to that question. This was a manual to support its products so almost anyone could grab this book and make good use of the tool.

I would say that’s a good resource, but the best resource—if you were into lettering design as I am, the best resource for me I discovered in college. It was a book called Lettering for Reproduction. And this is pre-computer so it was all on paper. But it was this great book that told you about the history of lettering, taught you about classifications and styles. It taught you how to actually think about lettering. It taught you all about the optical effects that determine how to draw letters and make them balanced. It was on its own a great lettering course. I was lucky enough to find that in probably first or second year of college.

That was really what taught me how to be a lettering designer, that one book: Lettering for Reproduction, written by a guy named David Gates, I believe. And I think you can still get it because I’m always recommending this book to people. They tell me that you can still find it. But that was an excellent book and I still refer to it from time to time.

Dan: That’s awesome. I’m picking up both of those immediately. Being interested in type at such a young age, do you feel that’s a curse in a way? Everywhere you go there’s lettering and fonts. I came into design and specifically typography later in life. It’s something I always had an appreciation for but never applied myself to it until later.

Now I almost feel a bit cursed. You’re not just absorbing the information. You’re looking at the design of the typeface. I’m curious if you’re drawing inspiration from things around you there or is it more I’d rather see less fonts than more? I’m curious what your take on that is.

Ian: I’m always getting inspiration from everything around me. I basically can’t get enough of it. It’s endlessly interesting to me. It’s funny, you were taking about at a young age coming across this. I’ve realized what I do now is I’m trying to express emotional qualities in a logo for people. Typically, that’s what I’m trying to do, make something feel joyful, serious, trustworthy, premium, whatever. And as a kid, you’d watch those World War II movies and they’d have some it’s be the Nazis and British, and you’d be in Germany with that really dense kind of threatening Fraktur style lettering.

I really felt that stuff. I felt the menace. I think I had this weird emotional connection with letters. I think everyone has that to an extent, but I think I have it to a large extent. I’m never tired of that, tired of the emotional effect that different letters and different arrangements can have. Luckily, I get to work with that all day, every day.

Dan: Lucky for us too because like I said, the work is everywhere. I think that’s what’s kind of incredible. In fact, when I first came across your portfolio, I have to admit I didn’t think it was real. There was just so many recognizable brands and logos that I know and everyone knows. Things that are lined up at the supermarket so I almost thought this must be someone that’s putting together a portfolio and they’re practicing putting it together.

Ian: Just copying and pasting.

Dan: Yeah. How could this be one person, and it says, “Ian Brignell, Lettering Design”. So you are a one-man show. Is that right?

Ian: Yeah, I am a one-man show but it’s very important to recognize that my clients are design studios and ad agencies. So my clients are creative directors and art directors. I’m doing a logo or an identity for someone who’s typically in charge of an overall program. So everything I do is a collaboration. I almost never work directly with the end user or the person who has the brand. In that sense, it’s always a collaboration. But yes, I work by myself. Mostly because I like things to be simple and I like to be 100 percent responsible for what I do.

Dan: Did you work with non-creative directors in the past and that was less fun or has only working with agencies and creative directors been a conscious thing that makes you more productive, and you’re able to bang out more work that way? Or is it just the way things fell into place for you?

Ian: Yeah. I think it’s just the nature of the work I do that the simplest way of doing the work is to go to the people who might need it, and who speak my language. And see, that’s the great thing is that I’m dealing with people who are basically like me, so there is no communication problem. We understand each other. We tend to have similar references when we talk about design, or styles, or emotional effect. So in that sense, it’s very easy, and it was really just the only way I could see of doing it.

As soon as you go directly to the company, to the person in the company who owns the brand, then you basically have to be a design studio, and you have to offer all the services. And I was really just interested in doing the lettering design itself.

I guess when I started to specialize, as a lettering and logo designer, the obvious thing to do was contact all the people I’d gone to college with who worked in studios. Because they knew me. They knew I was into this, and that I had some abilities. So those were my first stops, was to go and see my friends I’d gone to school with. Everything sort of took off from there.

Dan: So there’s no one to say this needs more pizazz or wow? They speak your language, so that must make working on this a lot easier, I would think.

Ian: It really is. There are very few communication problems and to me those can be the biggest problems in the business, poor communication or a communication gap. There’s very little of that, so it’s a very good job in that sense.

Dan: You do call yourself a logo, lettering, and font designer and not necessarily a typographer, even though you’ve started a foundry, IB Type. Is that a conscious thing too? Is it just semantics or is there something more behind that?

Ian: It’s pretty simple. I just feel typographers is a very general statement and description of anyone who works with type. That’s how I see it. So almost any graphic designer is a typographer because they’re using type as their raw material. It’s the basic building block, what they’re going to work with. To me that’s just a general term, whereas, what I do is very specific. I’m trying to manipulate the shapes of letters themselves to convey a particular emotional message.

Dan: I agree with you. That makes sense, and what you’re delivering to the client is in some cases an actual font, right?

Ian: Yeah. There are quite a few custom fonts that I’ve done directly for clients. That’s definitely part of the work.

Dan: One of the first things that came to mind going through your portfolio and being legitimately amazed at how many brands you’ve worked with, when you go to the grocery store, do you enjoy that or is it stressful to see your work everywhere alongside a bunch of other stuff? Or is it fun to see your work everywhere?

Ian: Oh, it’s fun. I love that. Part of the reason is because all these angst, and uncertainty, and any of those kind of things that you might be thinking about, I do that before I send the work out. When I go out and see something I did five years ago, it’s like great, glad to see that’s still up there. Do you know what I mean? They haven’t changed it. I’m really happy when it still exists. But I don’t stress about I should have done this or that. Once it’s done it’s done, and I really like to move on to the next thing.

I am obviously very careful and try to make sure that absolutely everything is nailed down, so I don’t have to look at it five years from later and regret things. Yes, it’s fun to go to the store, the beer store, the liquor store, the grocery store. I love seeing the stuff out there.

Dan: It must be mind blowing. Do you see things that bother you I like that and obviously it’s working? It’s been up there for five years, but there’s some sort of niggle you wish you’d done differently?

Ian: Mostly no. It’s kind of like what happens if a client sends me a layout and they’ve sort of done a placeholder, and say now we want you to develop this, refine it, and give it these qualities. Often you start to change that. Then do what they’ve asked and they say oh, we sort of like where we started, because you get locked into something.

That’s one of those pitfalls of design, is you do something, look at it over and over a number of times over a number of weeks, and you have a hard time getting beyond it to seeing what it might be. That’s part of my job, to take it somewhere else for good reasons. But yeah, once something is done, it’s solid and on the shelf, I tend to be pretty happy with it, to be honest.

Dan: That’s great. If you weren’t happy, that would be a tough swipe. You’d have to avoid about every product out there.

Ian: It would mean you were doing something wrong, I think.

Dan: Yeah.

Ian: You should be critical of your work. There may be times when I go oh, well, maybe this or that, but it doesn’t bother me. I don’t worry about it because also if I wasn’t—if I’m not better now than I was 20 years ago, there would be something wrong as well. There will be tiny things that I think oh, maybe that could have been a little heavier, or that could have been spaced a bit more or whatever. It doesn’t bother me. And if I look at it and think I couldn’t do that now, I’d be worried.

Dan: Great point. In terms of process, you talked about showing something to the client and the client is getting attached to an earlier revision you sent them. How does your process typically work? If you’re working with an agency or creative director, is it mostly you on your own until you’ve perfected things, and then you present it? I know I’m always interested in how designers present their work, whether they’re presenting options or just one thing, like the Paul Rand style. This is it. If you don’t like it, hire someone else kind of thing.

Ian: I absolutely don’t work that way. Again, I work as a collaboration with other people and other designers specifically. Usually it’s a case of here’s the logo we want you to help us with. Maybe you can show us four or five ideas. We’ll narrow it down from there. Maybe show one or two to our client, and then finish off whichever one they decide to use. That’s a fairly typical process.

I like to show things at an earlier rather than later stage. I like to share the stuff, and often I’ll send more than they’ve asked for. If I’ve seen other options I’ll explore them, send them so we can have a discussion. I can never be sure, despite the brief and despite what they’ve asked for, I can’t be sure which of the things I explored they’re really going to end up liking.

I would rather show them more at an earlier stage than do too much editing on my own. I think that’s part of the whole process, is we’re exploring something, so you might as well see as much as you can. These two ideas that I might have eliminated might have really interesting little details that we can build on.

They know—ultimately the creative director knows the client and project better than I do. So I always have to keep that in mind and trust that. I’d rather they see more because they’ve got a more global view of the whole project.

Dan: I think that’s a good way to work even outside of graphic design, just building websites for instance in my experience it’s always been the more sharing internally the better for iterating. I’m curious too, in terms of actual process on your end in creating the work, you mentioned at an early age you were drawing letters with pen or pencil and calligraphy. Is that still how you approach a project initially, or is it digital, analog? Is there a mix there?

Ian: Yeah, there’s a total mix. It depends on the project and the kind of lettering they need. If it’s going to be a script, I’ll often start on paper, often with pencil. Pencils are one of the best tools ever, different sizes, thickness, softness of pencil because you can do so much modulation with pencil just with pressure and speed. You can get all kinds of really great details and textures with a pencil.

But the other tool I really like is a flexible thumb pen. There’s a pen called the Namiki Falcon, which I use all the time. It’s a slightly broad nib, gold nib. It’s flexible, and I actually bought it from this place called Classic Fountain Pens. They can modify the nib to make it more flexible. I’ve got this really flexible nib and they adjusted the feed so the ink flows really freely. So when you press on this nib you get a nice wide, heavy line. You can have this great control between thick and thin lines with the pressure you put on the pen.

That’s great for scripts and general ideas because as soon as you have a modulation in the line like that you get this energy, which is quite crucial to do at the beginning of a project. You do that at the beginning with the sketch. You can carry that energy through. Whereas, sometimes people will bring you a project and say okay, this is kind of what we want. We’ve kind of got this idea for this logo, but we feel it’s kind of dead. We need to inject energy.

That’s much harder to do at the end of the process. So tools like pencils and these flexible pens help you to work quickly and get that energy in the first place. I’ll use those kind of tools, but everything ends up ultimately getting scanned into the computer, and then perfected and worked on in the computer, to be sent to the client. They always need vector art in order to be able to place the lettering into their layouts.

Dan: Are you taking care of that too in terms of preparing the vector?

Ian: Yeah, that’s all part of it. Sometimes, if it’s a very precise corporate logo, the whole thing will happen on the computer. It depends. Sometimes it’s a very close-in process where they know what they want it to look like but they know the details need to be finessed, or weights need to be finessed. In that case it all happens on the computer.

Although I have to say that sometimes, even when you’re working on a very straight-ahead corporate identity, sometimes I need to go to the side with a pencil and do a five-second sketch to work something out. That’s always part of the process. That’s the fastest way to work out little problems, is with a small, quick sketch with a pencil.

Dan: Are you a fan or not of tablet sketching?

Ian: Sure. I basically use everything I can. I use a tablet and stylus for pretty much all the work I do on the computer. Of course, I use Adobe Illustrator, and within that there’s lots of different tools you can use and program to behave the way you want. You can modulate weight, pressure, thickness, and all those kinds of things if you’re doing a brush stroke, for example. I use that for some things. I’ll use pencils and pens and markers on paper for other things, and also brush markers, which are really cool because they don’t really conform to any other tool. They don’t act like a brush, they don’t act like a pencil, so you get unique results using that kind of tool as well.

I’m open to almost any kind of tool. Sometimes I’ll use eyeliners or mascara brushes, whatever, to get an interesting result. But I’m open to everything. The cool thing about computers is that computers cause you to make interesting mistakes because of the way they work. You grab a vector point and you scale it when you didn’t mean to and suddenly there’s this really cool thing looking at you. Computers are cool because they introduce their own little quirks and you know, kind of personality as well.

Dan: I totally agree. Those happy accidents that happen can easily happen in Illustrator as opposed to paper. I’m curious about you work with so many well-known brands and well-established brands. Do your personal feelings about a brand ever come into play when you’re doing this? If you have a favorite ketchup but you’re doing the competition’s lettering, does that ever conflict?

Ian: I wouldn’t say I ever have existential qualms about what I’m working on. Every project you’re basically trying to make your client look as good as possible. Obviously it’s a real honor to work on some brands, especially things like working on Dove soap. That was one of those projects that was really exciting to me. I remember being a kid, watching TV and the Dove commercials would come on. Anything that was on TV was huge, and really important.

That was one of my earlier memories of television advertising, was Dove soap. I was really thrilled when that came along. I think that’s true of a lot of the big brands. Because they’re big and they’ve endured, I remember them as a kid, and that seems to give them more importance. It doesn’t mean I treat them any better or worse, but it does feel like a bit of an honor to work on those big ones. That’s for sure.

Dan: I’ll bet. There’s an amount of pressure, I guess on those, to keep the heritage in mind while you’re retooling something.

Ian: That’s true. And a certain responsibility. It would be nice to think you’re doing something that’s going to last and that truly represents the brand. That is a big part of what we’re doing, is trying to get that across and make it as permanent as possible. You can’t guarantee that it’s going to be permanent but I think that’s how you should view it. You’re trying to get it right once and make it stick.

Dan: That’s a good goal, for sure. You’ve just joined Dribbble recently. I thought I’d ask you about a couple shots you uploaded. Your first one was kind of an amazing one, the “Share a Coke” font project. For those that haven’t seen this, but you’ve probably seen it on Coke cans. Some names you can get on the Coke can and it says “Share with Dan” or “Share with Ian.” You’ve designed the font that these are made in. I think it’s interesting what you had to work with to create that.

Ian: That was an interesting project because it was a very quick, short-term project. What happened was this client in Australia sent me the Coke logo, just the word Coke and said, “My client wants to know if you can make this into a font.” I said, “Sure, I can do that.” He said, “How long will it take?” I said, “I’m taking off in a couple weeks going on holiday. So can it wait a couple of months?” He said no, so basically I had about a week to get that font done and sent to him so he could test it.

Basically I had four letters to work with so the task was to see what the characteristics of those four letters were. It was a very bold font, very high contrast, so big difference between thick and thin strokes. It was a hybrid Serif, which meant there were serifs on some strokes but not all of them. The K had this long serif that touched the E, and they wanted that as a feature on all the serifs. They wanted them touching as much as possible. Bearing that in mind, I designed the whole font with those characteristics.

Dan: It took only a week to do that?

Ian: Yeah. It was a pretty intense week. I have to say, but I often find that working on things like fonts when you have to do it intensely and quickly the result is often really good. I’m not exactly sure why. I guess it’s a question of focus that you just have to give it so much attention that it seems to work out. That’s happened on other font projects. A lot of the font projects have been very rushed because the end client has no idea how long it takes. They just want the font and want it soon. I’ve found that that’s not a bad thing, for me anyway.

Dan: To me, not being a font designer, but I think if there was an unlimited amount of time I’d be tweaking vector points all day and never being done with it.

Ian: I think ultimately that’s the case. There are so many working parts to it that you can revisit things forever. The hard deadline is not a bad thing. It’s true with my own fonts I’m working on, if there’s some I’m working on but I have not given myself an absolute deadline, it’s taking too long.

Dan: You could endlessly tinker with it. You had the four letters Coke, C-O-K-E. What would be the ideal four-letter word to build a font off of? Are there certain letters that if I have the R—I know I could riff off of that easier?

Ian: I think that some font designers would say yeah a lower case G and maybe a cap K. There are a few notions on what the ideal letters would be. But I figure if all we have are these four, the rest is up to me. I just go with it. I would say I don’t think it really matters. If it was a word like “look” that wouldn’t be a lot of information, but you’d just have to go from there, and keep checking back to the original letters, and make it work as best you can. It’s a creative process. A lot of subjectivity comes into it and you just have to try to make it all work, mesh, and make the letters agree with one another.

Dan: I suppose that’s more fun for you that way. You can put a lot of your personality into the letters that weren’t there.

Ian: Yeah.

Dan: I have a favorite letter of this set, and I’m curious if you have a favorite letter or letters?

Ian: What’s your favorite letter?

Dan: I have two. I really like the lower case Y. A couple of the letters have that sort of—I don’t know the term for it, but the wispy thing at the end.

Ian: The tapered descender there.

Dan: I love that and I like the capital D, not because it’s in my name, but like you said earlier it’s a hybrid. It’s part Serif and part Sans-Serif, and that really works in the D. It works with a lot of letters. It’s an interesting font. Do you have a favorite letter or letters?

Ian: It’s funny you should ask that because I would normally not have really thought about it but a couple years ago my wife and I were in Paris. We were walking down the street, and we see this bus shelter with a Coke ad. We walk up to it and my wife says, “Stand in front of this. We need to take a picture.” So I’m looking at the ad, and the name on it was Alix. I’m looking at the X going whoa, three years ago I designed this in a big hurry. I really do not remember designing the X that way but I really like it. I had this great moment of kind of appreciating what I’d done, having forgotten the actual design. I guess I’m going to say the lower case X was my favorite letter.

Dan: I love it. I love all of them actually.

Ian: Thank you.

Dan: Moving on to another one of your shots, the Budweiser label. Again, you’re uploading this and initial reaction to folks would probably be he’s just practicing uploading images. It’s amazing to me that you’re the one person behind the delivery of this. This is obviously a really iconic thing. Budweiser, you couldn’t get more American than that. We touched earlier about the responsibility and pressure of dealing with such an iconic thing. Was that apparent in the Budweiser project?

Ian: Yeah it was because a big part of that project was heritage. They were trying to express the heritage, the authenticity of the brand. It’s a brand that goes back to 1877. So there was all this historical material to work with from their archives. It was really impressive stuff. Yeah, you do feel a certain humility and responsibility in trying to mine that material and bring it to life in a more modern setting, and treat it all with a great deal of respect and refinement.

I drew all the type, every bit of type on that—the art director wanted it done from scratch, based on historical inputs from the Budweiser brand. All the illustrations were done by other people, and the overall conception was done by the studio, but yeah, all that type he wanted done custom. That was a great project because it was all this material to look at. Fascinating historical stuff, labels, boxes, old bottles with embossed type on them, old signs. It was a great immersion in the history of this very significant brand.

Dan: It must have been overwhelming to have all that material to pull from.

Ian: It’s a real treat and that’s one of the best parts of what I get to do, is that often people are sending me all this old archival stuff I would never see any other way. There’s so much great lettering that’s been done in the latter part of the 1800s, early 1900s. There was tons of great lettering, tons of people who were really good doing lettering. There’s a wealth of material basically from all periods of history but I find that period is especially good.

Dan: You think there’s a resurgence of that now or has it always been there? The art of lettering or hand lettering?

Ian: I think it’s having a resurgence now. Partly because of technology because people are able to share stuff, they’re able to look into historical work very easily. I think there is definitely a resurgence and interest in the sort of handmade and that feeds into the lettering realm, definitely.

Dan: That’s interesting you said that it’s because of technology. I think you’re right and I think that’s an interesting irony that technology is helping discovery techniques and artistry that’s older, maybe 100 or 200 years old. That’s great.

As a last question for you I wonder anyone listening to this is probably wondering how the heck did Ian do this and get so much good work under his belt. How did he find all these clients? How did they come to him? That’s a big question but moreover, any little tidbit of advice for the young lettering logo font designer? If there was one thing you could tell them to do to try to further and better themselves?

Ian: It’s interesting the way you framed that question. I think the best piece of advice would be respect your client. If I’m going to boil it down to one, it would be respect your client. I remember myself as a young person when I graduated from college. And the funny thing about college is that you’re given a project by your professor but then you’re kind of in charge.

You decide what it’s going to look like, how it’s going to evolve. You’re in charge and you get used to that. You’re the guy making the decisions and your opinion’s the one that matters. When you get out and start working, I think a lot of people I knew had a lot of clashes because they weren’t letting that go. I think respecting your client is probably the best thing you can do.

That means you’re going to pay attention to the brief, you’re going to respect the brief. You’re going to revisit it. You’re going to always keep that in mind because ultimately you’re there only because your client exists. That sounds like a business proposition and it is. I think that’s extremely important if you want to keep going and keep getting clients, making clients happy, that’s the single thing you have to do. Sounds obvious but I believe that’s what you have to do.

Dan: Respect the client, absolutely.

Ian: I think it’s the old conundrum, like people say are you an artist. I say no, I’m not an artist. I’m a designer. I’m going to meet the needs of someone else, design something that satisfies their requirements. I’m not an artist. An artist creates the subject matter and decides what the message is going to be. That’s different. I’m a designer and I think if you keep that in mind that’s a very good start.

Dan: I think that’s good advice for everybody, regardless of your level of skill, or where you are in your career. That’s fantastic. Ian, thanks so much again for chatting with us. This has been really fun. We’re such big fans and I think your name should be a household name much like the items you’re designing are household items.

Ian: I appreciate that. Thank you.

Dan: Where could people find you after this interview, so we can make sure people can keep following your stuff and different projects you’re working on?

Ian: They can find me on Dribbble. I’m going to be posting there for sure. They can find me at ianbrignell.com. That’s my portfolio site where all the work goes. Also they can find my fonts, my retail fonts at ibtype.com.

Dan: Fantastic. At ibtype.com you’re actually selling your fonts or some of them, which is great. Not only can we look at your good work but we can use it.

Ian: And have fun with it.

Dan: Thanks once again, Ian. This has been a pleasure. Keep up the great work.

Ian: I’ll certainly try. Thank you.